What

appears, at first glance, to be a bowl of Lifesavers on the living room

table in Kate Mulgrew’s Upper West Side apartment in New York is, in fact,

a small tureen of throat lozenges and cough drops. In effect, they are

lifesavers; they are saving the vocal chords that Mulgrew punishes night

after night portraying Katharine Hepburn this spring and summer in the

one-woman Broadway play Tea at Five. What

appears, at first glance, to be a bowl of Lifesavers on the living room

table in Kate Mulgrew’s Upper West Side apartment in New York is, in fact,

a small tureen of throat lozenges and cough drops. In effect, they are

lifesavers; they are saving the vocal chords that Mulgrew punishes night

after night portraying Katharine Hepburn this spring and summer in the

one-woman Broadway play Tea at Five.

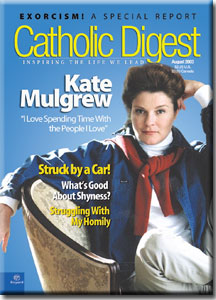

Portraying Kate, theater critics agree, is a natural for the 47-year-old Mulgrew, best known to legions of Star Trek devotees as Captain Kathryn Janeway of the Star Trek: Voyager series. Her husky voice resembles that of the mature Hepburn. Her features, particularly the cheekbones and light brown hair, remarkably mirror the Hollywood icon’s, though, at 5 feet 5 inches tall, Mulgrew is two inches shorter than Hepburn. The voice takes a beating, a consequence of what Mulgrew calls tricking. Mulgrew coerces her voice to drop two octaves from Act 1 to Act 2, to the throaty chortle of an elderly and sickly Hepburn. “To achieve Hepburn’s older voice, I must rub my vocal chords together and breathe through the voice box for support,” Mulgrew says. The lozenges, as well as soaking steam from a humidifier, are part of the daily ritual of keeping the vocal chords moist in preparation for each evening’s assault. The voice is as familiar to audiences as her face from her portrayal of Captain Janeway on TV from 1995 through 2001. People also remember her as Mary Ryan in the soap opera Ryan’s Hope and as Billy Crystal’s nemesis of a wife in the film Throw Mama From the Train.

The living room, comfortably furnished and overlooking West End Avenue, is decorated with paintings, several of them by her mother, Joan. Mulgrew, the eldest daughter among eight children born to T.J. and Joan Kiernan Mulgrew in Dubuque, Iowa, wears a thin white sweater, beige slacks and soft, slip-on shoes. With her hair pulled back, her complexion is noticeably flawless; her figure is trim at 110 pounds. She is attentive, answering a visitor’s questions thoughtfully as she sucks on the lozenge. Elsewhere in the roomy apartment, Alec Egan, 18, the younger of her two sons, is ambling down a hallway. Her older son, Ian, 19, is also home from college. Mulgrew’s husband, Tim Hagan, comes in from Cleveland, where he works, every two weeks or so.

She says she’s always felt an affinity with the Cistercian nuns of the Mississippi Abbey of Our Lady in Dubuque, also known as the Trappistines. “The not-knowing, spiritual quest is what intrigues me,” she says. “When I probed my dear friend Mother Columba, the Trappistine abbess, about the higher truths, namely ‘Does God exist?’ she paused briefly and with a half-smile said, ‘I have no idea, but I hope so.’ This, after 50 years of contemplative living, says it all.” Mulgrew grew up in affluence; her great-great grandfather, T.J. Mulgrew, was the first millionaire in Iowa. Still, she went to work at age 12. Mulgrew’s father worked in road-building until he sold his business. Her mother was an artist. Her parents are living, though her mother has Alzheimer’s. Two of Mulgrew’s sisters died young, one from a brain tumor and the other from pneumonia. Her youngest sister, Jenny, lives in New York. Encouraged from childhood by her mother in her desire for the stage, Mulgrew says, “She was my champion.” Her father, however, resisted. “I jumped a year in high school and left when I was 16,” she says. “I wanted to go to the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. My father pushed me to go to college. It was Clarke College in Dubuque, a Catholic college. When I was 17 or 18, I went to New York and got into the Stella Adler [School of Acting] master class at NYU.”

“I have a strong personality, so I never got any bimbo roles,” she says. “I’ve never been a movie star, and that probably saved me. When I was young, I wanted to do more movies. But destiny had other things in store, better for my disposition. My career has been one of leveling.” Despite the critically acclaimed fit, both physically and artistically, she doesn’t consider the role of Hepburn a trap, an image she can never shed. “Was Captain Janeway a trap?” she asks about her role in Star Trek. “Say what you will about parallels or likeness. I’m not exceedingly like Hepburn.” But, like the Hepburn of the play, living alone at her Fenwick estate in Old Saybrook, Connecti-cut, Mulgrew speaks of a fondness for solitude. She muses about having a home in the West of Ireland, near Bantry Bay, where she might write and indulge her love of reading, preferably biographies and autobiographies. The Confessions of St. Augustine is on her bedside table. Last year she conquered Marcel Proust. Her favorite novel remains War and Peace.

“We make such a big deal of it now,” says Mulgrew about child-rearing. “We’re saying, Let’s be friends with our kids. I say we do what we can and maybe they’ll catch on. One thing that always mattered to me about raising children was making sure they were kind. I worked hard to instill empathy. I was not hard as a disciplinarian — making sure they made their beds or were home by 10 — but I made sure they were kind to old people and children. I know they are kind.” CD ©2003 Catholic Digest |

On

performance days, Mulgrew rises at 6 a.m., reads with a cup of tea, and

then returns to bed until 10 a.m. She swims daily. At 3 p.m. she’s in bed

again, napping until 5, when she leaves for the theater.

On

performance days, Mulgrew rises at 6 a.m., reads with a cup of tea, and

then returns to bed until 10 a.m. She swims daily. At 3 p.m. she’s in bed

again, napping until 5, when she leaves for the theater.

Raised

in an Irish-Catholic family, Mulgrew says, “I believe in God and that Jesus

Christ is the Son of God. It is important to me to have a spiritual dimension

in my life. I like profound faith.”

Raised

in an Irish-Catholic family, Mulgrew says, “I believe in God and that Jesus

Christ is the Son of God. It is important to me to have a spiritual dimension

in my life. I like profound faith.”

Her

first career break — a role in Ryan’s Hope — came before she finished the

acting class. She played Mary Ryan from 1975 through 1977 and at the same

time landed the part of Emily Webb in a production of Our Town at the American

Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut. She did more work in television

— Mrs. Columbo, Cheers, Murphy Brown, and a 1981 miniseries, The Manions

of America. Her films include A Stranger Is Watching, Remo Williams, and

Throw Mama From the Train, and the 1980 A Time for Miracles, in which she

played the role of Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first American-born saint.

Her

first career break — a role in Ryan’s Hope — came before she finished the

acting class. She played Mary Ryan from 1975 through 1977 and at the same

time landed the part of Emily Webb in a production of Our Town at the American

Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut. She did more work in television

— Mrs. Columbo, Cheers, Murphy Brown, and a 1981 miniseries, The Manions

of America. Her films include A Stranger Is Watching, Remo Williams, and

Throw Mama From the Train, and the 1980 A Time for Miracles, in which she

played the role of Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first American-born saint.

Having

her sons with her right now pleases her. “I love spending time with the

people that I love,” she says. Juggling motherhood with acting when the

children were young, Mulgrew credits her live-in nanny of 19 years, Lucy

Ledezma, with abiding help in raising the boys. “I love to work, had to

work to pay the bills and raise the kids,” says Mulgrew, whose boys were

educated in Catholic schools. “I just hoped that at the end of the day

my sons would aspire to the example, rather than my complaints of the reality.”

Having

her sons with her right now pleases her. “I love spending time with the

people that I love,” she says. Juggling motherhood with acting when the

children were young, Mulgrew credits her live-in nanny of 19 years, Lucy

Ledezma, with abiding help in raising the boys. “I love to work, had to

work to pay the bills and raise the kids,” says Mulgrew, whose boys were

educated in Catholic schools. “I just hoped that at the end of the day

my sons would aspire to the example, rather than my complaints of the reality.”